The Origins & Early History of Suwannee County

Native Americans, Spanish, & The History That Formed Suwannee County

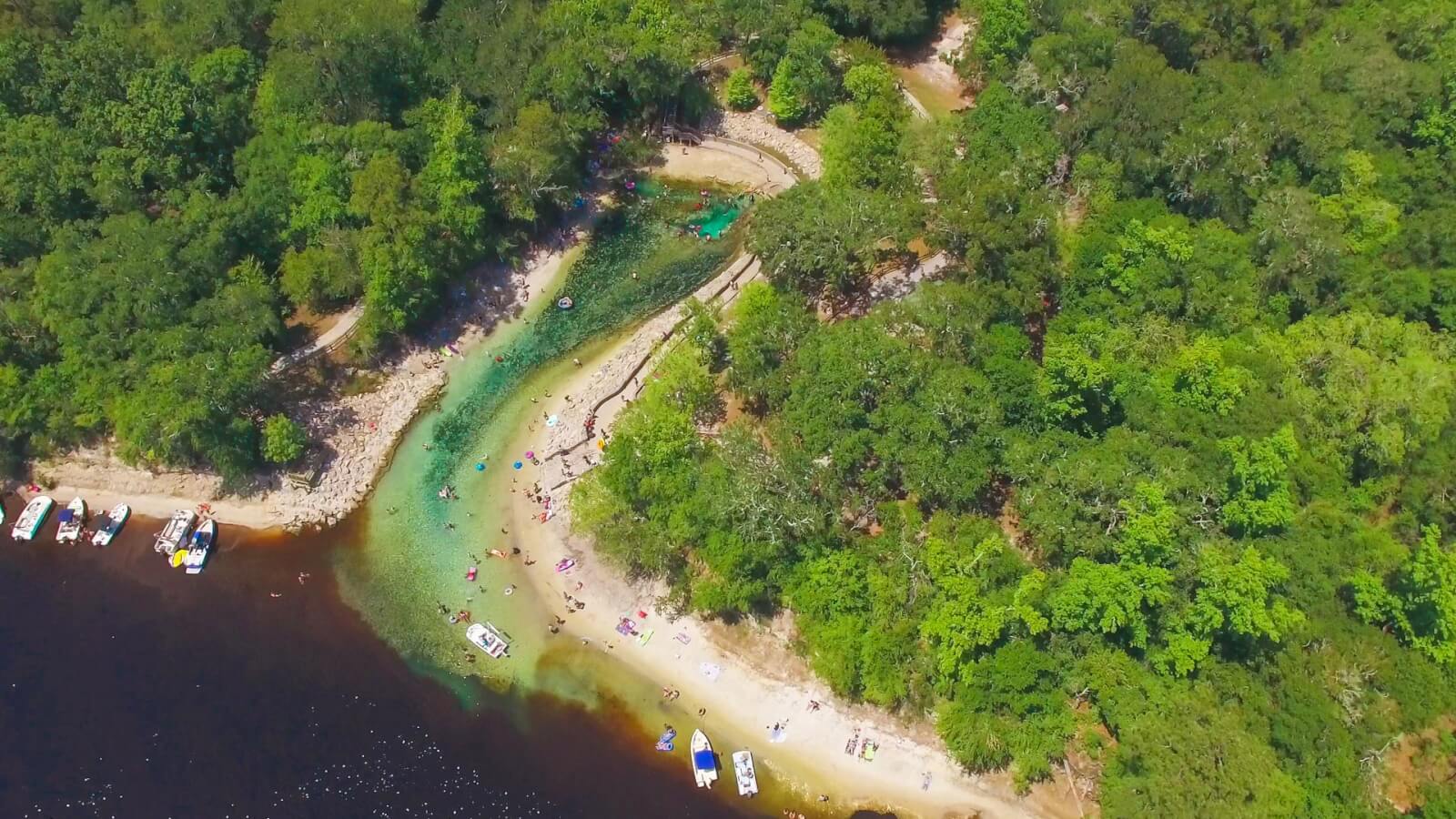

The melody and words to “Old Folks at Home”, better known as “Way Down Upon the Swanee River”, evoke visions of tranquility upon the old homestead, a return to simpler and quieter times. Written by anti-slavery songwriter Stephen Foster, the song reminds listeners of the United States’ checkered past while looking forward to a better future. Despite controversy over its history, it can rightly be said that “Old Folks at Home” is one of the most famous melodies in the world. The song, and the river for which it is named, are entwined with the history of Suwannee County.

Suwannee County, the thirty-seventh county created in the State of Florida, was formed on December 21, 1858 out of the western portion of Columbia County. The word “Suwannee” is sometimes thought to originate from the Native American word sawani, meaning “Echo River”, “Muddy Waters”, or something similar. A more probable origin is that it was based upon the Spanish name for the river, Rio San Juan de Guacara, which translates into the “River of Saint John of Antiquity”, referring to John the Apostle. As the Spanish gave way to English dominance, the old Spanish name was anglicized to become “Suwannee”. As Suwannee County is bounded on three sides by the famous river, it only made sense that the new county would be named in its honor.

The area that is now Suwannee County has been inhabited for thousands of years. Those inhabitants include the Deptford Culture, which flourished from about 800 B.C. to 700 A.D. It is characterized by sand-tempered pottery decorated with carved wooden paddles. Little evidence remains of this culture except for some burial mounds, shards of pottery, and remnants of the plants and animals they ate. Another local culture was the McKeithen Weeden Island culture, which flourished between 200 and about 750 A.D. The Weeden Island culture was superseded by the Suwannee Valley culture around 750 A.D. Eventually, the Timucua developed and dominated northern Florida and southern Georgia. We know more about the Timucua than previous Native American cultures because of written records from Europeans who met the Timucua during early expeditions and colonization of Florida. Unfortunately, the Timucua are one of the truly extinct tribes within the United States. The last recorded survivor of the Timucua, Juan Alonso Cabale, died in Cuba on November 14, 1767.

The first known Europeans to arrive in the area in and around Suwannee County was Spanish explorer Panfilo de Narvaez, who arrived with his group of some four hundred men in 1528 during an ultimately futile attempt to find treasure. Juan Velazquez, one of Narvaez’s officers, was the first recorded casualty of drowning in the Suwannee River. After charging into the river with his horse, both drowned. Only four members of the expedition survived to return to Spanish-held Mexico seven years later. One of the survivors was Cabeza de Vaca, who wrote a rather fanciful book detailing his journey that led others to explore Florida.

In 1539, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto traveled through Suwannee County on a journey that ultimately spanned some four thousand miles and took four years, although de Soto himself died in 1542 near the Mississippi River. De Soto fought a famous battle against hundreds of Timucua Indians in or near Suwannee County in 1539, very possibly near Live Oak. The location of this so-called “Battle of the Lakes”, “Battle of the Ponds”, or “Battle of Napituca” has never been located with certainty. In the battle and its aftermath, nine village chiefs and several hundred warriors were killed.

After de Soto’s expedition, Spanish influence gradually spread into Florida via Catholic missions and outposts. Several Spanish missions were established in Suwannee County in the early 1600s, including San Juan de Guacara, Santa Catalina de Afucia (also spelled “Afuyca”, “Ahoica”, or “Afuerica”), Santa Cruz de Tarihica, San Agustin de Urihica (sometimes spelled “Utoca”, “Niahica”, and later, “Axoyca”). The missions were tasked with converting the native Timucuas and provide a means of transportation and rest to travelers. The end of the Spanish mission system came about after a series of British raids originating from the Carolinas that occurred between 1702 and 1705 and destroyed many missions within inland Florida. Most survivors relocated closer to St. Augustine, and the interior of Florida was for the most part abandoned. The remains of missions and other cultural sites were enveloped by the wilderness, to be discovered by archaeologists centuries later. The Spanish lost Florida to Great Britain after the Seven Years’ War (called the French and Indian War by Americans) in 1763, at which time the few remaining Timucua either intermingled with the Seminole Indians or left with the Spanish.